Start Simple

The riders of yesteryear had to deal with arduous and finicky starting procedures.

Riders today have it easy. There was a time when riding a motorcycle was much more demanding; a time when the rider performed many of the tasks that a modern bike’s ECU, or computer, performs while riding, and before even starting it. Many more — ahem — experienced riders will remember a time when going for even a short ride was preceded by a complex ritual. Fortunately, those days are behind us, and riding a motorcycle has become mechanically much simpler.

If you own a modern motorcycle and want to go for a ride, you just turn the key, push the start button, and off you go. Heck, some riders don’t even need to turn anything on; with the key fob in your pocket, just hop on and push the start button. Simple starting, high reliability and low maintenance free up more time to spend on the road, and no one is going to complain about that.

The first thing any engine needs to start and run properly is the correct air-to-fuel ratio. The amount of fuel needed to maintain the right ratio changes, however, depending on engine and ambient temperatures: a cold engine needs a lot of fuel to start, and requires less fuel as it warms up. When you turn on the ignition on a modern fuel-injected motorcycle, various sensors send information to the bike’s ECU, which then feeds the engine the correct air/fuel ratio based on the data received. All of this is programmed into the ECU at the factory, and it is designed to maintain the optimum mixture over a very wide temperature range.

The first thing any engine needs to start and run properly is the correct air-to-fuel ratio. The amount of fuel needed to maintain the right ratio changes, however, depending on engine and ambient temperatures: a cold engine needs a lot of fuel to start, and requires less fuel as it warms up. When you turn on the ignition on a modern fuel-injected motorcycle, various sensors send information to the bike’s ECU, which then feeds the engine the correct air/fuel ratio based on the data received. All of this is programmed into the ECU at the factory, and it is designed to maintain the optimum mixture over a very wide temperature range.

None of this existed decades ago. The air/fuel ratio was governed by a carburetor, which had fixed jets that provided a mixture that worked best (far from perfect, actually) when the engine was at operating temperature, in a temperate climate, and at sea level; if any of those factors varied greatly, the bike ran poorly. Any long-term variation in sea level or average temperature required that the carburetor be re-jetted. The ignition spark advance, which is done automatically now, was once controlled manually, by the rider, via a twistgrip on the left handlebar, or by a lever.

Starting was also affected by temperature, and the rider had to follow a specific procedure to feed the engine the correct mixture. The owner’s manual for a 1943 Harley-Davidson WLA, for example, had more than two pages dedicated solely to the start-up process. The components required to start bikes like the WLA included the fuel petcock, choke lever, throttle, spark advance, clutch and kick starter, all of which had to be utilized in a specific way and order.

After turning on the petcock to feed fuel to the engine, and making sure the transmission was in neutral and the clutch engaged (a foot clutch did not return on its own), a rider had to first prime the engine to give it an initial dose of fuel: set the choke to fully closed (choking the air and enriching the mixture), turn the throttle wide open, and kick the starter a couple of times with the ignition off so the engine could gulp some raw fuel. Some bikes simplified this by including a tickler on the carburetor; a small button which, when depressed, would push on the float, thus flooding the carb and feeding the cold engine with raw fuel.

Then, with the ignition turned on, the choke was backed off to partially closed (or the tickler tickled), the left grip twisted all the way back for full advance, the throttle cracked open a touch, and the rider then attempted to start the bike with “vigorous strokes of the foot starter.” If the engine didn’t fire after three vigorous strokes, the priming and starting processes were repeated until it did. Of course, this procedure varied depending on engine temperature, and a rider had to be very familiar with it so as not to flood the engine with fuel, which would then make it nearly impossible to start. A rider also had to keep pushing on the kick starter when it reached the bottom of its stroke until the engine either started, or stopped spinning, otherwise a backfire could put out a knee.

Then, with the ignition turned on, the choke was backed off to partially closed (or the tickler tickled), the left grip twisted all the way back for full advance, the throttle cracked open a touch, and the rider then attempted to start the bike with “vigorous strokes of the foot starter.” If the engine didn’t fire after three vigorous strokes, the priming and starting processes were repeated until it did. Of course, this procedure varied depending on engine temperature, and a rider had to be very familiar with it so as not to flood the engine with fuel, which would then make it nearly impossible to start. A rider also had to keep pushing on the kick starter when it reached the bottom of its stroke until the engine either started, or stopped spinning, otherwise a backfire could put out a knee.

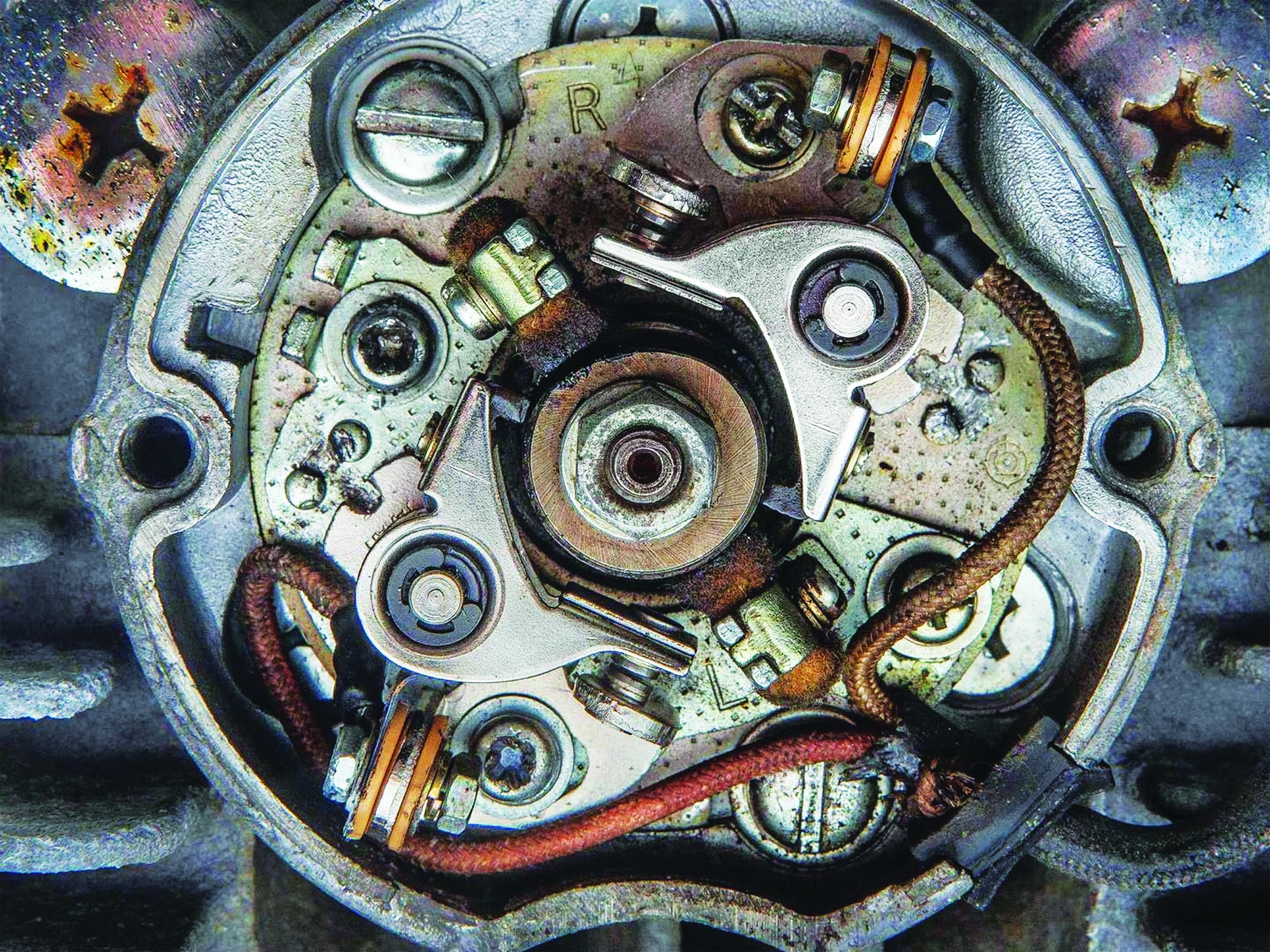

Following the procedure outlined in the owner’s manual didn’t always work, so a rider had to know the intricacies of their particular machine, and adjust the ritual accordingly, or the bike would refuse to fire. It was actually a pretty good theft deterrent for the day. And, of course, the bike had to be in a very good state of tune, which was also labour-intensive — points and spark plug gaps had to be set regularly; necessary gaskets and seals had to be in good condition so water wouldn’t infiltrate the ignition system and lead to lots of vigorous kicking.

Aren’t you happy your bike is fuel-injected?

Thanks for Reading

If you don’t already subscribe to Motorcycle Mojo we ask that you seriously think about it. We are Canada’s last mainstream motorcycle magazine that continuously provides a print and digital issue on a regular basis.

We offer exclusive content created by riders, for riders.

Our editorial staff consists of experienced industry veterans that produce trusted and respected coverage for readers from every walk of life.

Motorcycle Mojo Magazine is an award winning publication that provides premium content guaranteed to be of interest to every motorcycle enthusiast. Whether you prefer cruisers or adventure-touring, vintage or the latest models; riding round the world or just to work, Motorcycle Mojo covers every aspect of the motorcycle experience. Each issue of Motorcycle Mojo contains tests of new models, feature travel stories, compelling human interest articles, technical exposés, product reviews, as well as unique perspectives by regular columnists on safety or just everyday situations that may be stressful at the time but turn into fabulous campfire stories.

Thanks for considering a subscription. The Mojo team truly appreciates it.