Tough Nut to Crack

Troubleshooting isn’t always as straightforward as it first seems.

This was a tough one. My friend Carl, who I’ve mentioned here before, has a large collection of 1970s and ’80s Japanese motorcycles. Once in a while, he’ll pull one out of the “to-do” section of his garage and hand it over to me for a complete mechanical refurbish. Once completed, the bike then goes into the “ready-to-go” section, and it gets ridden. However, he sometimes slips one in that is already being ridden but might need a little tweaking, or maybe a small leak has developed, or some other mechanical anomaly has stricken the machine.

The latest of his motorcycles to grace my shop is a 1980 Suzuki GS1000S. The bike was introduced in 1979 and produced for only one more year, with only a small number being sold in North America. This was the dawn of the superbike era, when riders like Eddie Lawson, Freddie Spencer and Wes Cooley mounted highly modified, high-handlebarred 1,000 cc monsters on relatively skinny tires, and wowed spectators across the U.S. in the feature AMA Superbike class.

The GS1000S was known unofficially as the Wes Cooley replica because of its blue and white paint scheme and bikini fairing, which mimicked the Yoshimura race bike on which Cooley took the 1979 and 1980 AMA Superbike championships. Sadly, Cooley, who was a hero of mine, passed away last October.

The reason the GS is in my shop is because it had a nagging problem. While it would start up instantly and run fine when cold to moderately warm, it would run poorly when hot, stumbling when cracking the throttle off idle, refusing to accelerate smoothly, and eventually fouling the spark plugs. The bike had been gone over by someone else, and by all accounts, everything seemed in order.

My first instinct was to check the condition of the engine by performing a leakdown test. When Carl bought the bike, he’d been told by the seller that the engine had been refreshed and that it was in excellent condition. The leakdown confirmed that the seller wasn’t fibbing; the results were among the best I’ve seen in a long time, with between two and four per cent loss among the cylinders, which is excellent.

While the GS1000S produced about 90 hp and was a performance marvel at the time, it nonetheless featured some dated technology, including a contact-point ignition system. Carl wants to keep the bike as original as possible, so he did not want to swap out the points with an aftermarket electronic system, and in any case, when well-adjusted and maintained, points can do the job quite well.

Static timing (checking the timing with the engine off) seemed fine, though there was a tiny discrepancy between the two sets of points (one set fires cylinders 1-4, the other 2-3). With the points set properly, the next step was to check the timing with a timing light and the engine running. This provides a more precise picture of the actual timing. It’s at this stage that I stumbled upon the real problem.

A timing light is powered by a vehicle’s battery, and picks up the signal of a spark with an inductive sensor placed over the spark plug wire. When it senses a spark, it fires a strobe which, when aimed at the engine’s timing marks, freezes them visually, making it easy to see the actual timing of the engine.

A timing light is powered by a vehicle’s battery, and picks up the signal of a spark with an inductive sensor placed over the spark plug wire. When it senses a spark, it fires a strobe which, when aimed at the engine’s timing marks, freezes them visually, making it easy to see the actual timing of the engine.

With the timing light strobing away, I could see that the timing was just a couple of degrees off, so I began adjusting it. However, as I did this and the engine warmed up, the strobe light began flashing erratically, before eventually shutting off completely. The engine still ran, albeit a bit roughly, so I swapped out the timing light sensor from the number one to the number two cylinder, thus picking up the signal from another coil. Alas, the strobe worked again, for a while at least, before shutting off again. Suspecting the timing light, I tested it on my pickup truck and it strobed away strongly.

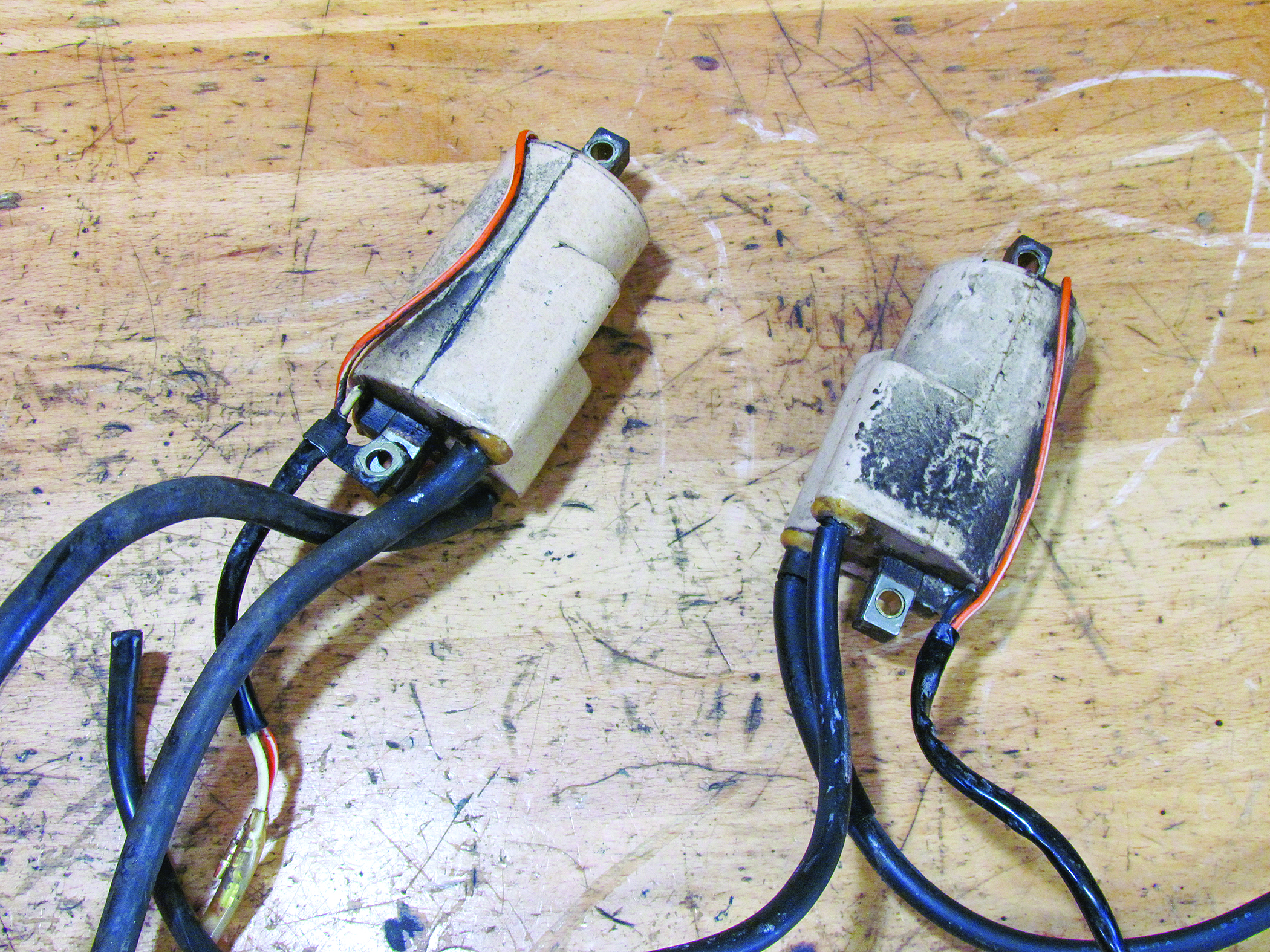

Then came my uh-huh moment. The ignition coils were faulty. Cold, they were fine, but as they heated up, the spark got too weak for the timing light sensor to pick up. The spark weakened — not to the point to where the engine would not run, but enough that the mixture would not combust completely, thus eventually fouling the plugs.

Well, a few days later and with a new set of aftermarket coils installed, the engine immediately sounded crisper. The timing light also worked properly, and with the timing set and the idle mixture adjusted properly (it had been difficult to adjust with a weak spark), the bike ran flawlessly, hot or cold. It is now ready for delivery back to Carl’s, thus freeing up some shop space for the next challenging round of troubleshooting.

Thanks for Reading

If you don’t already subscribe to Motorcycle Mojo we ask that you seriously think about it. We are Canada’s last mainstream motorcycle magazine that continuously provides a print and digital issue on a regular basis.

We offer exclusive content created by riders, for riders.

Our editorial staff consists of experienced industry veterans that produce trusted and respected coverage for readers from every walk of life.

Motorcycle Mojo Magazine is an award winning publication that provides premium content guaranteed to be of interest to every motorcycle enthusiast. Whether you prefer cruisers or adventure-touring, vintage or the latest models; riding round the world or just to work, Motorcycle Mojo covers every aspect of the motorcycle experience. Each issue of Motorcycle Mojo contains tests of new models, feature travel stories, compelling human interest articles, technical exposés, product reviews, as well as unique perspectives by regular columnists on safety or just everyday situations that may be stressful at the time but turn into fabulous campfire stories.

Thanks for considering a subscription. The Mojo team truly appreciates it.