My Beloved Atlas

If I have to explain, you might not understand.

It was a simple question, really, asked by someone unfamiliar with shop machinery. We were talking about my workshop when I mentioned I had a lathe. “What’s a lathe?” he asked. I told him it’s a machine on which I can work metal. He then asked exactly what I did with it. And that’s when it got complicated.

According to the Oxford Paperback Dictionary, a lathe is “a machine for holding and turning pieces of wood or metal etc. against a tool that shapes them.” While that describes succinctly, if rather crudely, how a lathe functions, it doesn’t say what you can actually do with it.

At 12 x 36 inches, my Atlas lathe is moderately sized. It has a six-inch swing, which means the maximum diameter of a workpiece is 12 inches (the first number in the size); the length of the bed (the second number) determines the maximum length of said workpiece, at 36 inches. Atlas 3000-series lathes enjoyed a long production life, beginning in 1957, with the last one reportedly leaving the factory on March 6, 1981. My Model 3986 lathe was manufactured in Kalamazoo, Michigan, on November 17, 1971 by Atlas Press Company, but it was sold under the Craftsman name by Sears. Yes, Sears once sold lathes.

My lathe came accessorized with a quick-change gearbox, which allows me to choose from 54 feed speeds for the carriage (it contains the cutting tool holder), and enables SAE thread-cutting capability. I also have a number of chucks, including a four-jaw chuck that allows cutting of offset workpieces, a milling attachment, and numerous other attachments that really expand its uses. It was also upgraded at one point with a turret tool post, which is a more solid and versatile cutting tool holder than the standard one.

My lathe came accessorized with a quick-change gearbox, which allows me to choose from 54 feed speeds for the carriage (it contains the cutting tool holder), and enables SAE thread-cutting capability. I also have a number of chucks, including a four-jaw chuck that allows cutting of offset workpieces, a milling attachment, and numerous other attachments that really expand its uses. It was also upgraded at one point with a turret tool post, which is a more solid and versatile cutting tool holder than the standard one.

I have a long history with this lathe, having first acquired it with my late friend, Denis Lavoie, when we opened our bike shop in 1992. Although I later went on to other things, Denis continued shop operations, though he let me use the lathe on occasion. I bought it back from him in 2018, after he closed the shop due to failing health. The first thing I made after setting it up in my workshop at home was a set of hub-centric adapters for my pickup, to centre a set of aftermarket wheels onto its hubs. It has since turned out a number of useful parts for me, as well as some indispensable tools.

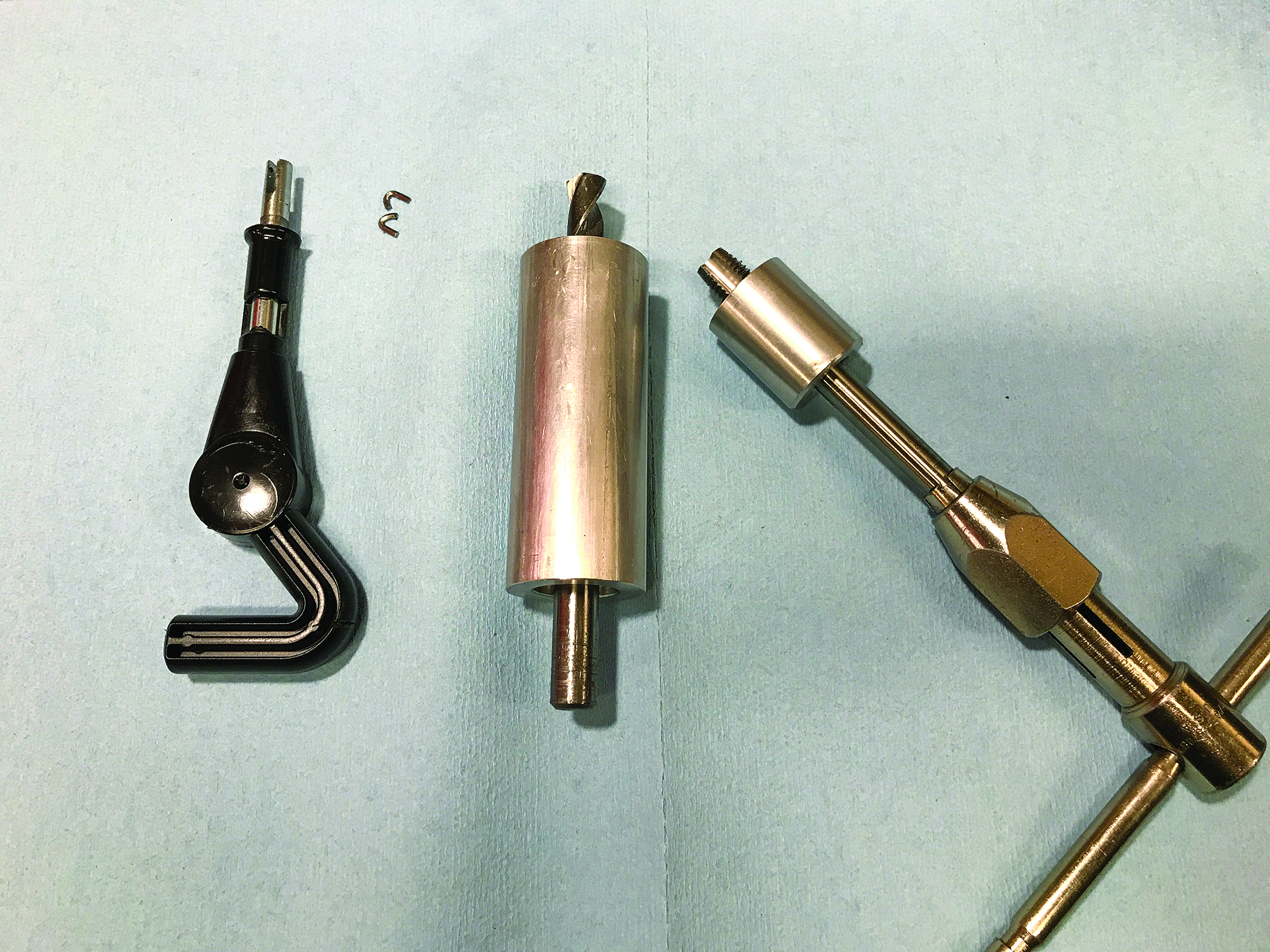

When a friend of mine had a leaking head gasket on his BMW R1100GS, it was unfortunately discovered that a pair of cylinder studs were pulling out of the crankcase, due to previous improperly performed top-end work. The fix was simple enough: install thread inserts to repair the damaged crankcase threads, which required drilling the damaged threads out, tapping the holes with oversized threads, and screwing the inserts into the newly cut threads. Not so simple was the task of installing the thread inserts perfectly square into the crankcase, otherwise the studs would not be perfectly perpendicular to the gasket surface — and that’s a problem. To achieve this, I machined a pilot that sat flat on the crankcase surface and guided the drill bit squarely into the hole. I also made a pilot to guide the tap, so it wouldn’t cut crooked threads.

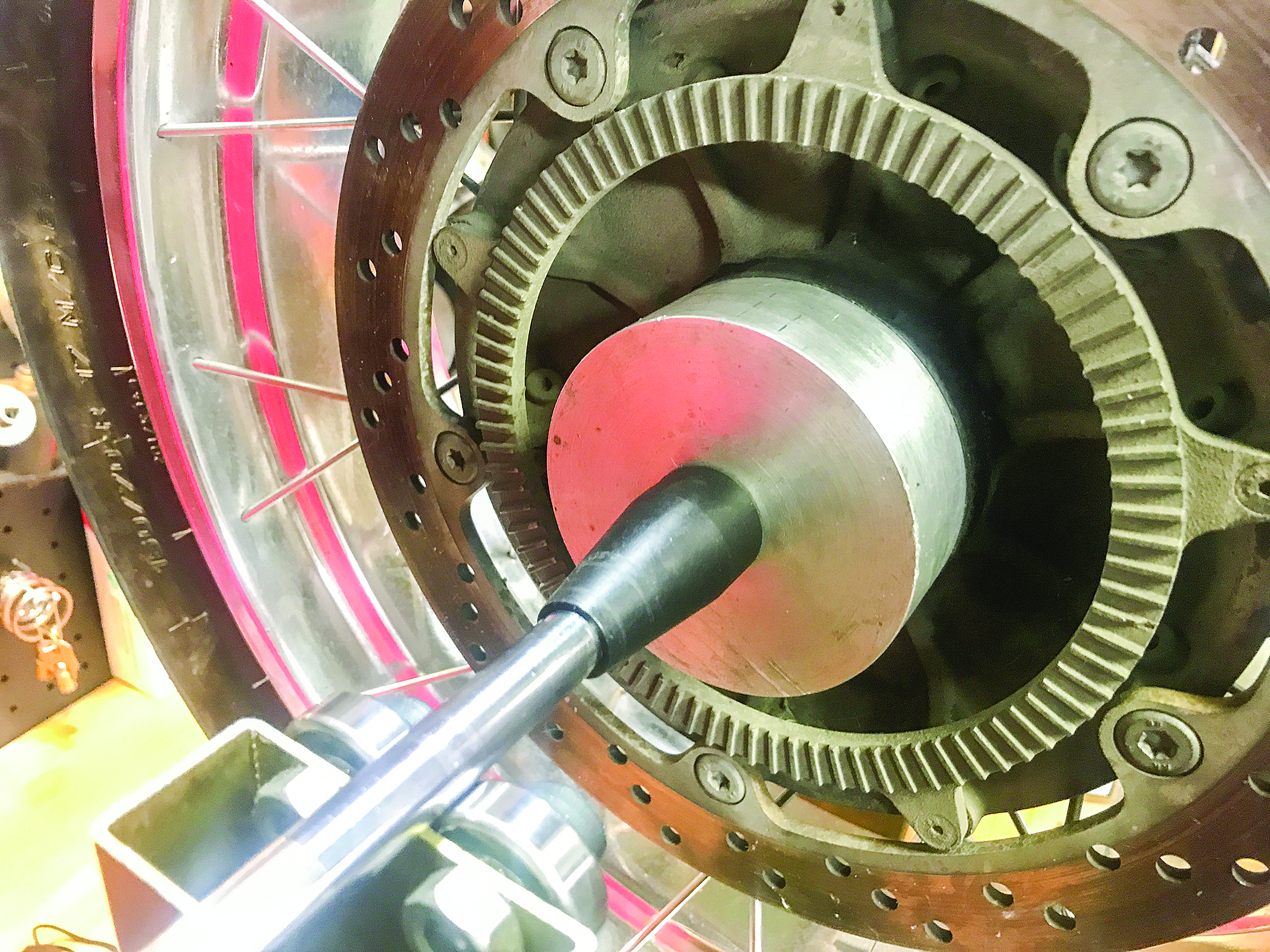

In addition, I installed a new set of tires on the same bike. I’m equipped to install and balance tires, but when it comes to the latter, my static balancer uses a shaft that passes through a wheel’s bearings. The GS has a single-sided swingarm with a car-like, stud-mounted rear wheel, with no bearings. Had it not been for my Atlas, the wheel would have gone unbalanced. However, going through my stock of metal scraps (another item acquired from Denis), I found an appropriately sized piece of aluminum, cut and drilled it into shape on the lathe, and proceeded to balance his rear wheel, as well as any other GS rear wheel I might encounter in the future.

In addition, I installed a new set of tires on the same bike. I’m equipped to install and balance tires, but when it comes to the latter, my static balancer uses a shaft that passes through a wheel’s bearings. The GS has a single-sided swingarm with a car-like, stud-mounted rear wheel, with no bearings. Had it not been for my Atlas, the wheel would have gone unbalanced. However, going through my stock of metal scraps (another item acquired from Denis), I found an appropriately sized piece of aluminum, cut and drilled it into shape on the lathe, and proceeded to balance his rear wheel, as well as any other GS rear wheel I might encounter in the future.

My most recent acquisition, the Honda PC50 you read about in the last issue, needed front suspension service. The original 47-year-old bushings in its leading-link fork were worn out, causing the front wheel to flop about. While I found online sources for replacement bushings, they were made from plastic, like the originals. Atlas came to the rescue, again, and I machined a set of bushings from aluminum, as well as the bronze inserts to go inside of them. The Honda’s front-end is now as solid as new, and will likely stay that way for even longer than the original.

Unlike the dictionary description, I found it hard to explain to my guest exactly what I did with my lathe. Next time someone asks, I’ll just show them instead.

Technical articles are written purely as reference only and your motorcycle may require different procedures. You should be mechanically inclined to carry out your own maintenance and we recommend you contact your mechanic prior to performing any type of work on your bike.

Thanks for Reading

If you don’t already subscribe to Motorcycle Mojo we ask that you seriously think about it. We are Canada’s last mainstream motorcycle magazine that continuously provides a print and digital issue on a regular basis.

We offer exclusive content created by riders, for riders.

Our editorial staff consists of experienced industry veterans that produce trusted and respected coverage for readers from every walk of life.

Motorcycle Mojo Magazine is an award winning publication that provides premium content guaranteed to be of interest to every motorcycle enthusiast. Whether you prefer cruisers or adventure-touring, vintage or the latest models; riding round the world or just to work, Motorcycle Mojo covers every aspect of the motorcycle experience. Each issue of Motorcycle Mojo contains tests of new models, feature travel stories, compelling human interest articles, technical exposés, product reviews, as well as unique perspectives by regular columnists on safety or just everyday situations that may be stressful at the time but turn into fabulous campfire stories.

Thanks for considering a subscription. The Mojo team truly appreciates it.