Never Look a Gift Bike in the Mouth

Sometimes another person’s description of a motorcycle is far different than what you end up seeing in person.

If you’re a regular Motorcycle Mojo reader, you know I have an affliction. I can’t stop acquiring new motorcycles. I’ve reduced my visits to online classified ads so that I can avoid impulsive bike purchases, and I even thought that my recent purchase of a new Triumph would be enough to hold me off for a while. But then, a couple of months ago, I got a text message from my good friend, Dimitri. “I got a 1959 Ariel Huntmaster 650 … but I don’t want it anymore. Do you know anyone who’s willing to take it on?” I replied saying I didn’t know anyone off hand but asked about condition and price so that I could pass on the info.

“It’s in parts. I have the complete bike with gaskets and a complete front end off another bike … If someone wants to take it on, I’ll pass it on.”

Before my eyes even finished scanning his text message, my fingers had already typed a reply: “Dude! I’ll take it!” It seems that I’m wired to accept any motorcycle that I consider a good deal — and a free bike, even if it’s delivered in a basket, is a good deal. Sometimes.

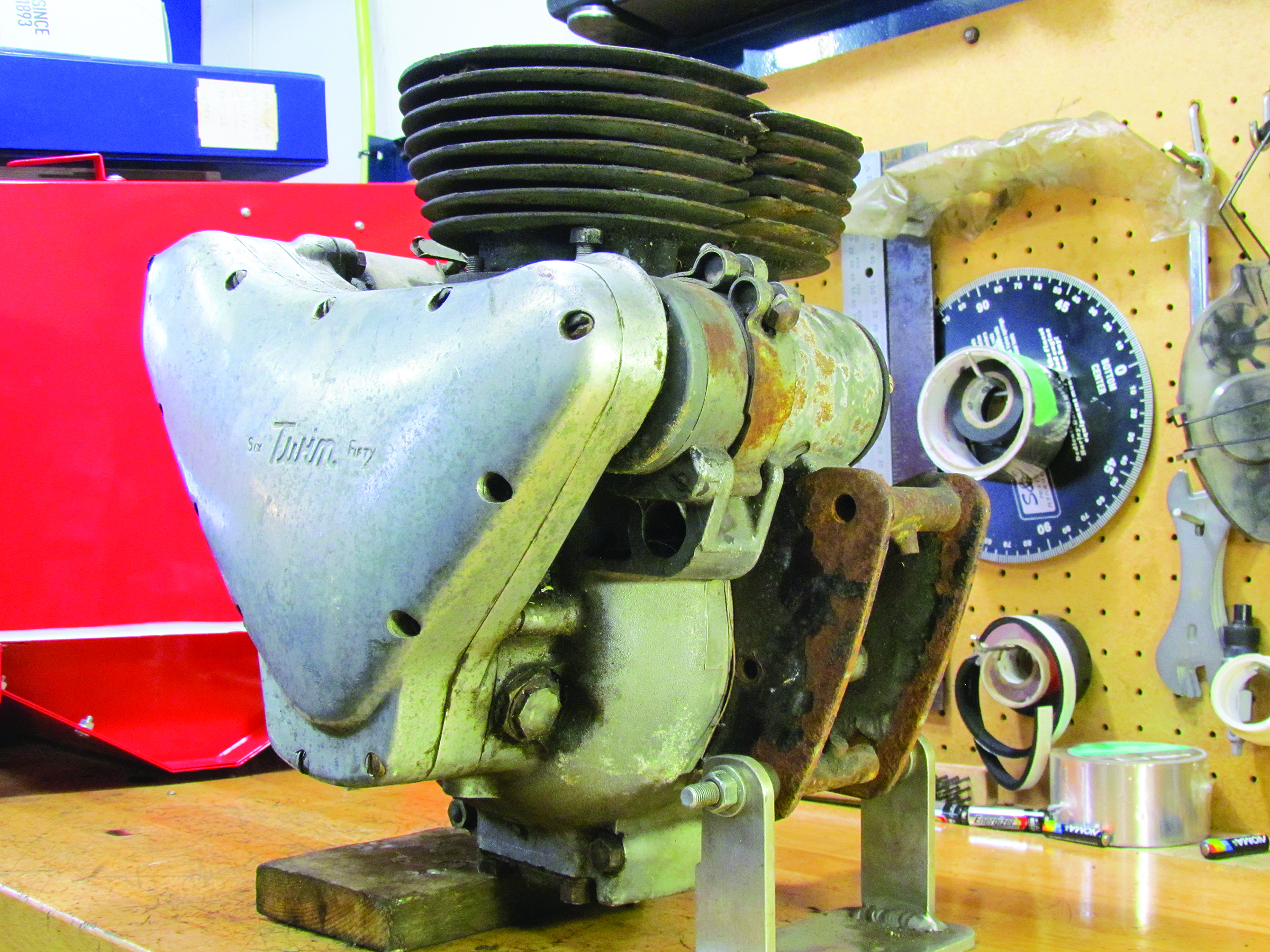

I’d never heard of the Ariel Huntmaster. I knew of the British bike maker, famous mostly for its Square Four motorcycles, but I had to research my latest acquisition. Its official model designation is the Ariel FH 650 Huntmaster, built between 1954 and 1959. It’s powered by a 646 cc parallel-twin with pushrod-actuated overhead valves, cast iron cylinder and head, and a single Amal carburetor. The engine connects to a separate four-speed gearbox via an enclosed primary chain. A kick start fires it up, a six-volt dynamo provides electrical power and maintains battery charge, and a magneto produces the spark. The electrical system is by Lucas (I can hear you older guys laughing …), which was sketchy even in the best of times.

I do not know the provenance of the bike, other than that Dimitri had taken it as payment for some construction work he’d performed for someone, and that it sat in a basement in that person’s home for many years. That owner had taken it apart to restore it, but had put the project aside at some point and never got around to finishing it. Dimitri had also told me that, while it sat in that basement, it had unfortunately suffered some flood damage, or at least the parts of it that sat on the floor.

I do not know the provenance of the bike, other than that Dimitri had taken it as payment for some construction work he’d performed for someone, and that it sat in a basement in that person’s home for many years. That owner had taken it apart to restore it, but had put the project aside at some point and never got around to finishing it. Dimitri had also told me that, while it sat in that basement, it had unfortunately suffered some flood damage, or at least the parts of it that sat on the floor.

We arranged that I pick it up on Saturday morning a few days after our initial text exchange. In that time, I found pictures of the bike online, and saw that it looked like a classic Brit bike of the era, and it was rather attractive. Preparing myself for the worst by anticipating to find it in rough shape, I was nonetheless dismayed to discover that it was in really rough shape. Spread out on his front porch, it looked like metallic roadkill.

I gathered the parts and put them in my pickup, and from what I saw, it did, in fact, look complete. The engine was complete, except for the cylinder head, which had been removed and disassembled. The primary case, chain, and clutch were all accounted for, as was the transmission. The frame, swingarm and, as promised, two sets of forks were there, as well as all of the smaller bits, like electrical components, bodywork, seat, shocks, and wheels.

After unloading the parts into my garage, I took a quick inventory of stuff I didn’t see. The most obvious was the handlebar and one exhaust pipe. Less obvious, but still critically important, were one intake valve and all of the valve keepers. And nearly as critical: half of the valve retainers and valve-spring seats, and numerous brackets, fasteners and other items were corroded beyond being serviceable.

Even closer inspection revealed a heavily corroded fuel tank that someone in the past had tried to repair with fibreglass, a stuck, gummed-up speedometer, and rusty wheels with a few broken spokes. Despite being rusty and stripped of paint, the frame and swingarm were in otherwise excellent condition.

Even closer inspection revealed a heavily corroded fuel tank that someone in the past had tried to repair with fibreglass, a stuck, gummed-up speedometer, and rusty wheels with a few broken spokes. Despite being rusty and stripped of paint, the frame and swingarm were in otherwise excellent condition.

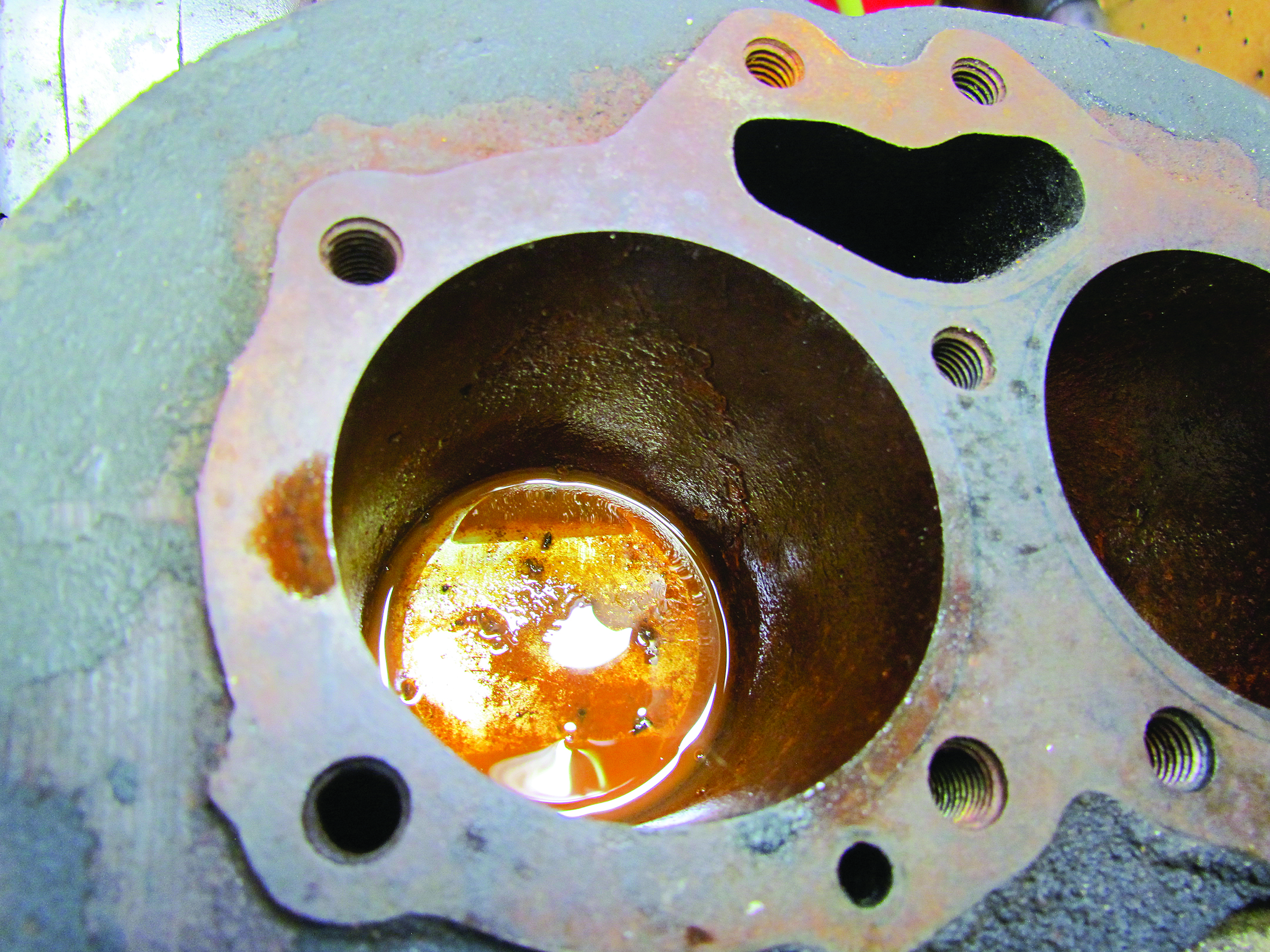

The biggest issue, though, was with the engine, which was one of the items that sat on the floor of that flooded basement (it’s absurdly heavy, so I see why). It was seized solid. The cylinders had since been soaking in penetrating oil, and I hope that one day the pistons will slide through. Even if I can take the engine apart, I’m afraid that sourcing critical components will be extremely difficult.

While I enjoy restoring motorcycles, and my plan is to hopefully get this Huntmaster running one day, for now I’ve also put the project aside. I will, however, take measures to ensure that corrosion doesn’t further take a toll.

Technical articles are written purely as reference only and your motorcycle may require different procedures. You should be mechanically inclined to carry out your own maintenance and we recommend you contact your mechanic prior to performing any type of work on your bike.

Thanks for Reading

If you don’t already subscribe to Motorcycle Mojo we ask that you seriously think about it. We are Canada’s last mainstream motorcycle magazine that continuously provides a print and digital issue on a regular basis.

We offer exclusive content created by riders, for riders.

Our editorial staff consists of experienced industry veterans that produce trusted and respected coverage for readers from every walk of life.

Motorcycle Mojo Magazine is an award winning publication that provides premium content guaranteed to be of interest to every motorcycle enthusiast. Whether you prefer cruisers or adventure-touring, vintage or the latest models; riding round the world or just to work, Motorcycle Mojo covers every aspect of the motorcycle experience. Each issue of Motorcycle Mojo contains tests of new models, feature travel stories, compelling human interest articles, technical exposés, product reviews, as well as unique perspectives by regular columnists on safety or just everyday situations that may be stressful at the time but turn into fabulous campfire stories.

Thanks for considering a subscription. The Mojo team truly appreciates it.