Reconnecting With The Past

Perusing an online buy-and-sell website leads to a bike build long forgotten

Editor Glenn Roberts and I have in the past discussed our impulse to reconnect with our youth. In biker terms, this means reacquiring a motorcycle (or more) that has some significance to us emotionally. Last summer, Glenn bought a near-mint 1981 Yamaha XS650, which he told me is almost exactly the same model as the first street bike he owned, give or take a model year. A year ago, I too acquired what had been my first street motorcycle, an extra-clean, low-mileage Honda FT500 Ascot.

We both came across our respective retro-bikes quite accidentally: Glenn through an acquaintance; I while leisurely perusing classified ads with no intention to buy. I do this to kill time on occasion, and to read the sometimes comical, sometimes ridiculous claims some sellers make when trying to pawn their rides.

Finding a Piece of History

While again glancing through online classifieds recently, I came across a picture that froze me in my browsing. Within the tiny thumbnail preview picture I saw a machine that took but a millisecond to recognize, and it brought back a wave of memories. Clicking on the image, the description was very brief, mentioning some of its easily recognizable parts, stating (erroneously) that it had an aluminum frame, and that only 200 were built. I’m not sure where that last part came from, but there is in fact only one such bike in existence. And as the larger images confirmed, it was indeed a bike I had built more than 20 years ago.

While again glancing through online classifieds recently, I came across a picture that froze me in my browsing. Within the tiny thumbnail preview picture I saw a machine that took but a millisecond to recognize, and it brought back a wave of memories. Clicking on the image, the description was very brief, mentioning some of its easily recognizable parts, stating (erroneously) that it had an aluminum frame, and that only 200 were built. I’m not sure where that last part came from, but there is in fact only one such bike in existence. And as the larger images confirmed, it was indeed a bike I had built more than 20 years ago.

Before I became a motorcycle journalist, I had been a motorcycle mechanic. I’d worked in a few dealerships prior to starting my own business in 1994 with partner and friend Denis Lavoie. We didn’t sell motorcycles; we were instead equipped with a modest machine shop that we used to build engines and bikes for our customers.

New Shop, New Build

One of the first projects we took on after opening was for the service manager of the Montreal Harley dealer where I used to work before taking off on my own. He wanted to build a Sportster-based dirt tracker for the street, a style now known as a street tracker. The dealer where he worked just wasn’t equipped for the type of fabricating work required to take on such a project, which is why we were handed the contract.

One of the first projects we took on after opening was for the service manager of the Montreal Harley dealer where I used to work before taking off on my own. He wanted to build a Sportster-based dirt tracker for the street, a style now known as a street tracker. The dealer where he worked just wasn’t equipped for the type of fabricating work required to take on such a project, which is why we were handed the contract.

Working at a Harley dealer has other perks, however, one of them being access to crash-damaged bikes. He bought a crashed 1986 Sportster 883, which would become the donor bike. Of course, to make a proper street tracker – lightweight, svelte and with the appropriate dirt-track look – a proper dirt-track frame had to be procured.

The connection to the frame at the foundation of the street tracker came via Lavoie’s brother, Martin. Martin was an AMA-licensed Canadian flat-track racer living in Florida. He was a regular on the American flat-track circuit, making the finals more often than not, with a race victory at the Daytona short track in 1983, and an AMA national win at Sturgis in 1985. His bike of choice, of course, was the legendary Harley-Davidson XR750, a bike that is currently on display at L’Épopée de la Moto, a motorcycle museum in St-Jean-Port-Joli, just east of Quebec City on Hwy 132. But I digress.

An XR Coming Together

Martin provided the bent 1972 Harley XR750 frame, which became the basis of the street tracker. That the frame was bent was of no concern, because the top tube had to be modified anyway to provide clearance for the taller 883 engine. The entire top frame tube was removed, as were the two front downtubes, each of which was cut off between the two forward engine-mounting holes. New chrome-moly tubes were repositioned and welded in place. Unfortunately, because the top tube had to sit taller to clear the cylinder heads, the reworked frame lost its unique cross-tube steering-head layout, a characteristic of true XR750 frames where the backbone meets the steering neck at the bottom and the front tubes cross the backbone to join the steering neck at the top.

Martin provided the bent 1972 Harley XR750 frame, which became the basis of the street tracker. That the frame was bent was of no concern, because the top tube had to be modified anyway to provide clearance for the taller 883 engine. The entire top frame tube was removed, as were the two front downtubes, each of which was cut off between the two forward engine-mounting holes. New chrome-moly tubes were repositioned and welded in place. Unfortunately, because the top tube had to sit taller to clear the cylinder heads, the reworked frame lost its unique cross-tube steering-head layout, a characteristic of true XR750 frames where the backbone meets the steering neck at the bottom and the front tubes cross the backbone to join the steering neck at the top.

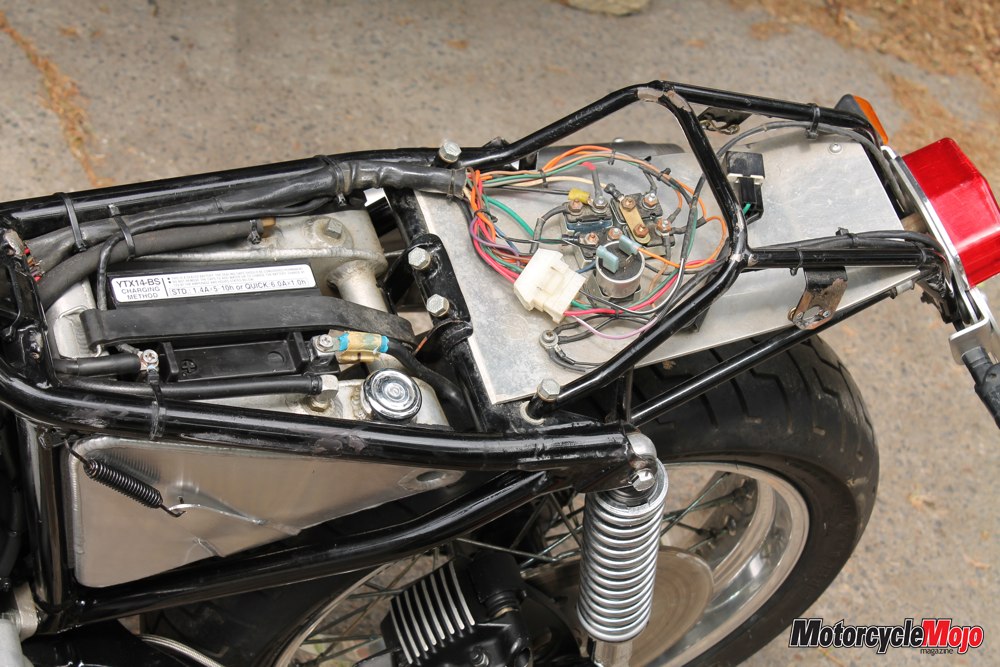

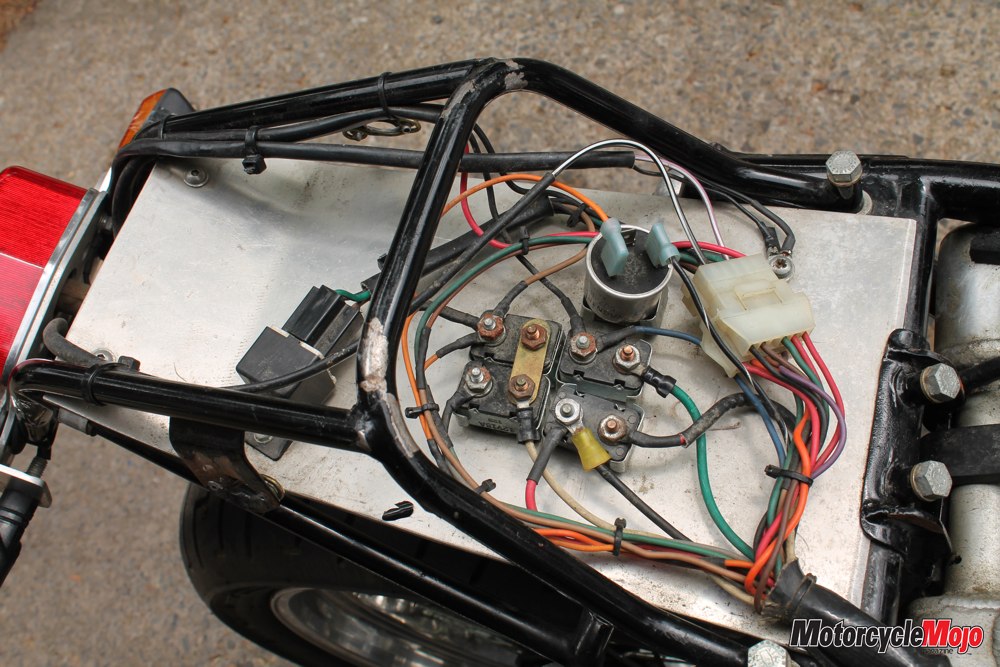

To remain faithful to the XR750, an aluminum oil tank was fabricated, though it is larger than the original tank, because incorporated within its centre is a battery box. It was hand-fabricated by Montreal-based custom-bike builder Dave Cody, who had a genius eye for bike design and a surgical hand with a TIG welder. The tailpiece is an aftermarket XR750 item made of fibreglass; the swingarm is not the original tubular item, but a square-tube item that came off an Ironhead Sportster. Because the 35 mm fork on the 1986 donor bike was bent, a 39 mm fork assembly from a later model was used. The entire wiring harness was handmade by yours truly, and designed to be almost invisible. The wire wheels were laced up using stock hubs and 18-inch aluminum rims: an Akront in the front and a Sun in the rear. The peanut gas tank came off the donor bike, and Cody painted the bike, finishing it with hand pinstriping and gold-leaf lettering.

The engine was bored to 1200 cc, high-performance Screamin’ Eagle cams were installed, an S&S carburetor replaced the original Keihin, and the heads were converted to a twin-sparkplug setup. The engine probably makes about 90 hp.

If memory serves, it took the better part of our first season in business to build the bike, and it would often draw the attention of our other customers. It was informally considered the signature bike of Cosden Specialities, the name of our fledgling shop, comprising the first three letters of our first names.

Lost and Found

After six years, I went on to other things, while Denis can still be found machining and welding away at the shop. We had lost track of our beloved XR Sporty, which the service manager sold to someone in Quebec’s Eastern Townships a couple of years after it was built. I even delivered the bike to the new owner, but had never seen it again after that –until it popped up on my computer screen, just a few hundred pixels wide. The image immediately took me back to that summer of ’94, sawing, grinding and welding steel to earn my living, and loving it.

The day after I spotted the XR in the classified ad, I called Sherbrooke Harley-Davidson, the dealer that had acquired the XR on trade, and made an appointment to see it. I got there before noon that day. I had told Alex Guyon, the sales rep I’d spoken to over the phone, that I had a keen interest in the bike.

Unbeknownst to me, the bike had been on display in the showroom for about a year as a showpiece. Many people had inquired about it during that time, but Guyon filtered its potential buyers, weaning out those asking if they could add a passenger seat or put on a set of drag bars or, worse yet, chrome it, pointing them instead to other bikes in the showroom. He well understood it was more significant a machine than that, and that it needed to be handed over to someone who also understood.

The XR Goes Home

Before I arrived, he had prepared a sheet listing all the modifications made to the bike, perhaps to justify its asking price. He told me the name of the person who’d traded it in, and it was indeed the same person from the Eastern Townships to whom I’d delivered the bike. I also learned that the bike spent the majority of its life on display in the guy’s basement, which explains why the speedometer, which was new when the bike was built, reads only 553 miles (it was a U.S. part incorrectly installed on a new bike and salvaged from warranty claims). It also explains why the bike still rolls on the Dunlop K591s I levered onto the rims so long ago. Guyon was completely dumbfounded when I confirmed these details, and even corrected him on occasion, including telling him details like the fact that the original front fender and hand-built exhaust had since been replaced – you see, I had neglected to mention over the phone that I had built the bike. When I did tell him though, the outcome was obvious. The Sporty XR had to come home.

I put the bike in a trailer after the snow melted and brought it back to Montreal. The bike is in excellent condition, though 20 years of storage has nonetheless taken a small toll. There are various chips in the frame paint, and the tailpiece, which I remember being a tight fit, sports two stress cracks, one on either side. The tires, which are barely worn in, need replacing because the sidewalls are cracked.

Aside from these repairs, I will also replace the gas tank. The peanut tank was chosen by the original owner, but I will source a replica XR750 gas tank so my XR Sporty becomes even more faithful visually to the machine on which it is modelled. Once these mods are complete, I can assure you I will not let it slip away again.

Thanks for Reading

If you don’t already subscribe to Motorcycle Mojo we ask that you seriously think about it. We are Canada’s last mainstream motorcycle magazine that continuously provides a print and digital issue on a regular basis.

We offer exclusive content created by riders, for riders.

Our editorial staff consists of experienced industry veterans that produce trusted and respected coverage for readers from every walk of life.

Motorcycle Mojo Magazine is an award winning publication that provides premium content guaranteed to be of interest to every motorcycle enthusiast. Whether you prefer cruisers or adventure-touring, vintage or the latest models; riding round the world or just to work, Motorcycle Mojo covers every aspect of the motorcycle experience. Each issue of Motorcycle Mojo contains tests of new models, feature travel stories, compelling human interest articles, technical exposés, product reviews, as well as unique perspectives by regular columnists on safety or just everyday situations that may be stressful at the time but turn into fabulous campfire stories.

Thanks for considering a subscription. The Mojo team truly appreciates it.