The Two-Stroke Engine

I have a confession to make, and it will probably shock many of you, so please hold off on the hate mail: I’m not a fan of two-strokes. There, it’s out in the open. I don’t really care for them, and certainly don’t share the affection that many riders have for those smelly buzzers. It’s curious, really, since the first few motorized two wheelers I ever owned were two-strokes. I began riding on a Motobecane moped; my first motorcycle was a CZ250 dirt bike; and my first race bike was a Suzuki RG500. I should therefore enjoy those noisy, smokey motorcycles. Or maybe those are the very reasons I don’t like them.

My disdain for two-strokes should be unfounded, really. They are lighter and more powerful than their four-stroke equivalents, and they have fewer moving parts. They are easier to service, since they do not require regular valve adjustments — though they do need a top-end refresh much more often than four-strokes. The upside of that last point is that a two-stroke top-end rebuild is much easier to perform, and less costly, too.

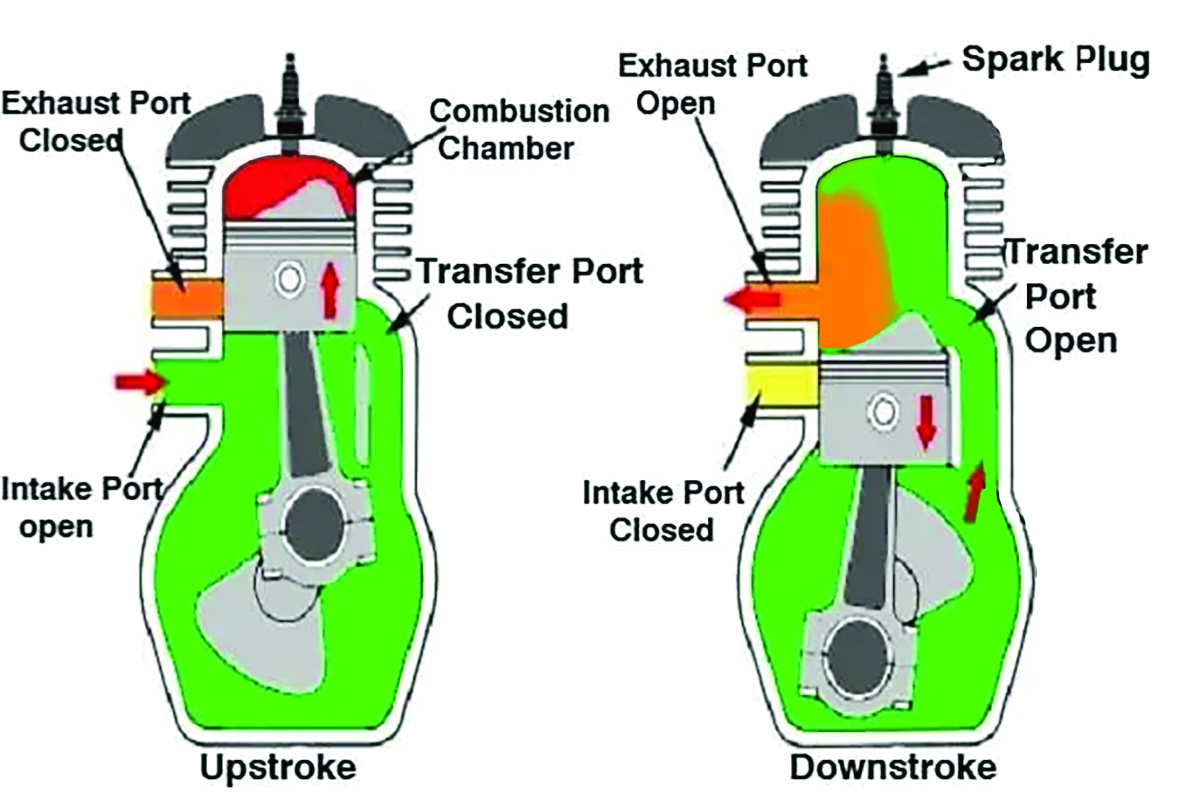

Two-strokes are more powerful than four-strokes because they have a power stroke on every revolution, and there are fewer frictional losses since they don’t have a power-sapping valve train. They are, however, not as thermally efficient as four-strokes.

For starters, the intake mixture enters the combustion chamber through ports in the cylinder, therefore, the piston only begins to compress the mixture well past the time it begins its upward stroke, resulting in a much lower compression ratio compared to a four-stroke.

For starters, the intake mixture enters the combustion chamber through ports in the cylinder, therefore, the piston only begins to compress the mixture well past the time it begins its upward stroke, resulting in a much lower compression ratio compared to a four-stroke.

A Yamaha RD350LC, which was a high-performance bike in its time, has a compression ratio of 6.3:1. A Honda CB450T from the same era has a compression ratio of 9.1:1. More compression equals more power. Despite the RD350’s smaller displacement, however, it produced two more horsepower than the Honda, and was much quicker because it weighed a whopping 82 lbs less.

Another reason they are less efficient is because they don’t have valves; they use the intake mixture to push the burnt gasses out of the combustion chamber through the cylinder ports, and therefore do not evacuate exhaust as efficiently as four-strokes. A higher percentage of burnt fuel remains in the combustion chamber, thus contaminating the fresh intake mixture and reducing its efficiency. Also, some of the unburnt fuel mixture follows the burnt mixture out of the cylinder and into the exhaust pipe. This is why two-stroke exhaust systems are fat in the middle; called an expansion chamber, the fat part is designed to help further evacuate exhaust gasses from the cylinder.

Of course, reduced thermal efficiency combined with power strokes that arrive at every revolution of the crankshaft mean that a two-stroke also uses more fuel; using the examples above, the Honda claimed 4.4L/100 km (53 mpg US) vs 5.5 L/100 km (43 mpg US) for the Yamaha.

Two-strokes are also inherently less durable. Unlike four-stroke engines that have oil pumped throughout their internals, two-strokes rely on oil carried in their fuel mixture to lubricate piston walls, piston pins and engine bearings. While effective at lubricating the engine, this system consumes a lot of oil, most of which is burnt during the combustion process (hence a two-stroke’s smokiness), and is also prone to causing premature engine failure if the fuel mixture or fuel/oil ratio are not correct.

In older two-strokes, a rider had to calculate the amount of oil to mix into the fuel with every fill up, and it had to be right. Too much oil would cause the spark plugs to foul and the engine to stall; not enough oil would cause the piston to seize, which is harder to remedy than a fouled plug. Later two-strokes eliminated the mental calculations by incorporating an oil injection system that used a pump to feed oil from an oil tank. This was a much better system, though it still needed some maintenance, as the oil pump had to be adjusted to feed the correct amount of oil.

In older two-strokes, a rider had to calculate the amount of oil to mix into the fuel with every fill up, and it had to be right. Too much oil would cause the spark plugs to foul and the engine to stall; not enough oil would cause the piston to seize, which is harder to remedy than a fouled plug. Later two-strokes eliminated the mental calculations by incorporating an oil injection system that used a pump to feed oil from an oil tank. This was a much better system, though it still needed some maintenance, as the oil pump had to be adjusted to feed the correct amount of oil.

Maybe my dislike of two-strokes originates from those first ones I owned; my first moped seized, probably because I got the oil mixture wrong; and my CZ250 regularly fouled spark plugs, which I think was actually a design feature, as it had two spark plugs and only one wire, so you could swap it to the working plug when the other one fouled. I do still like working on two-strokes, as evidenced by my latest project.

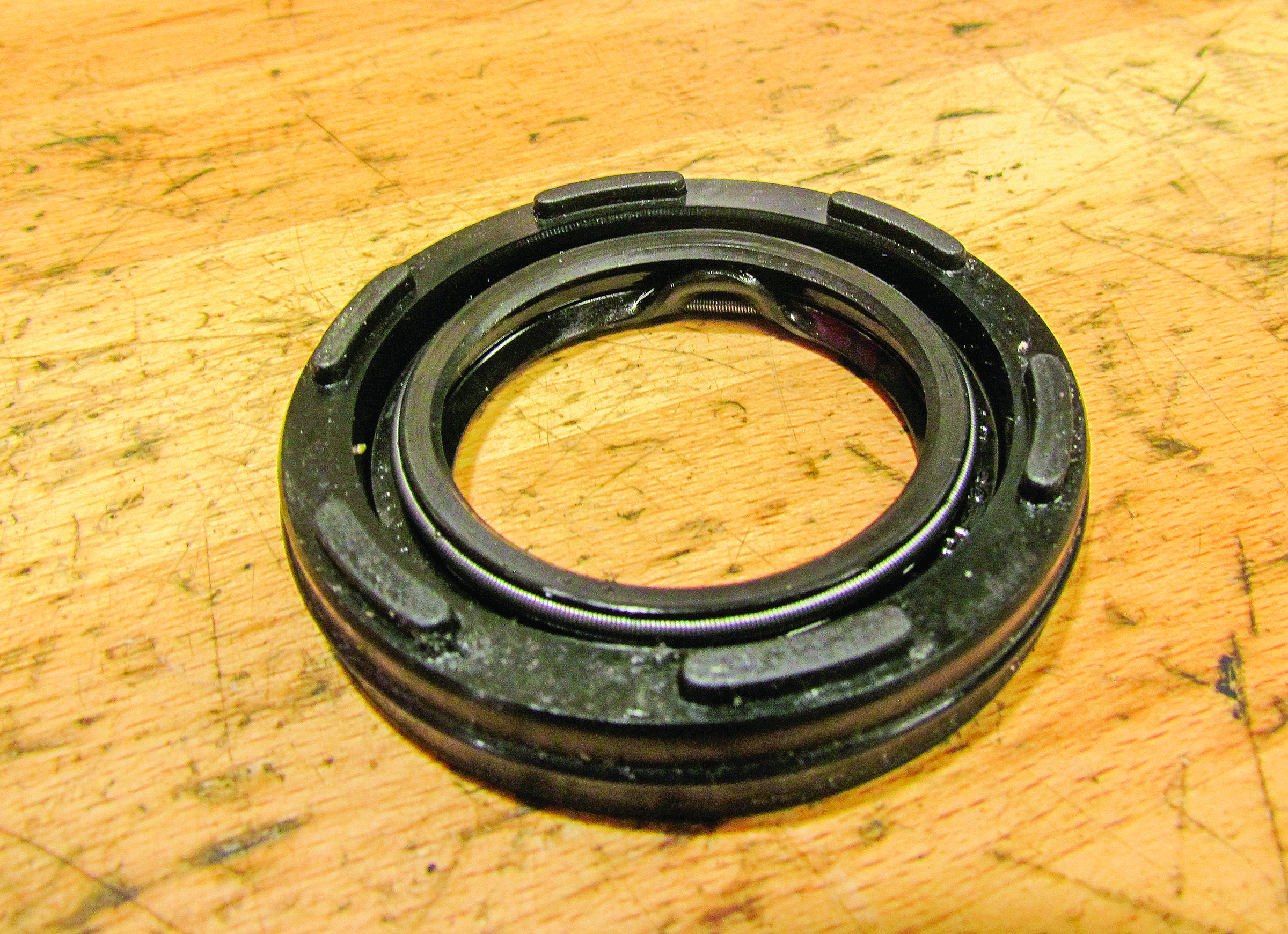

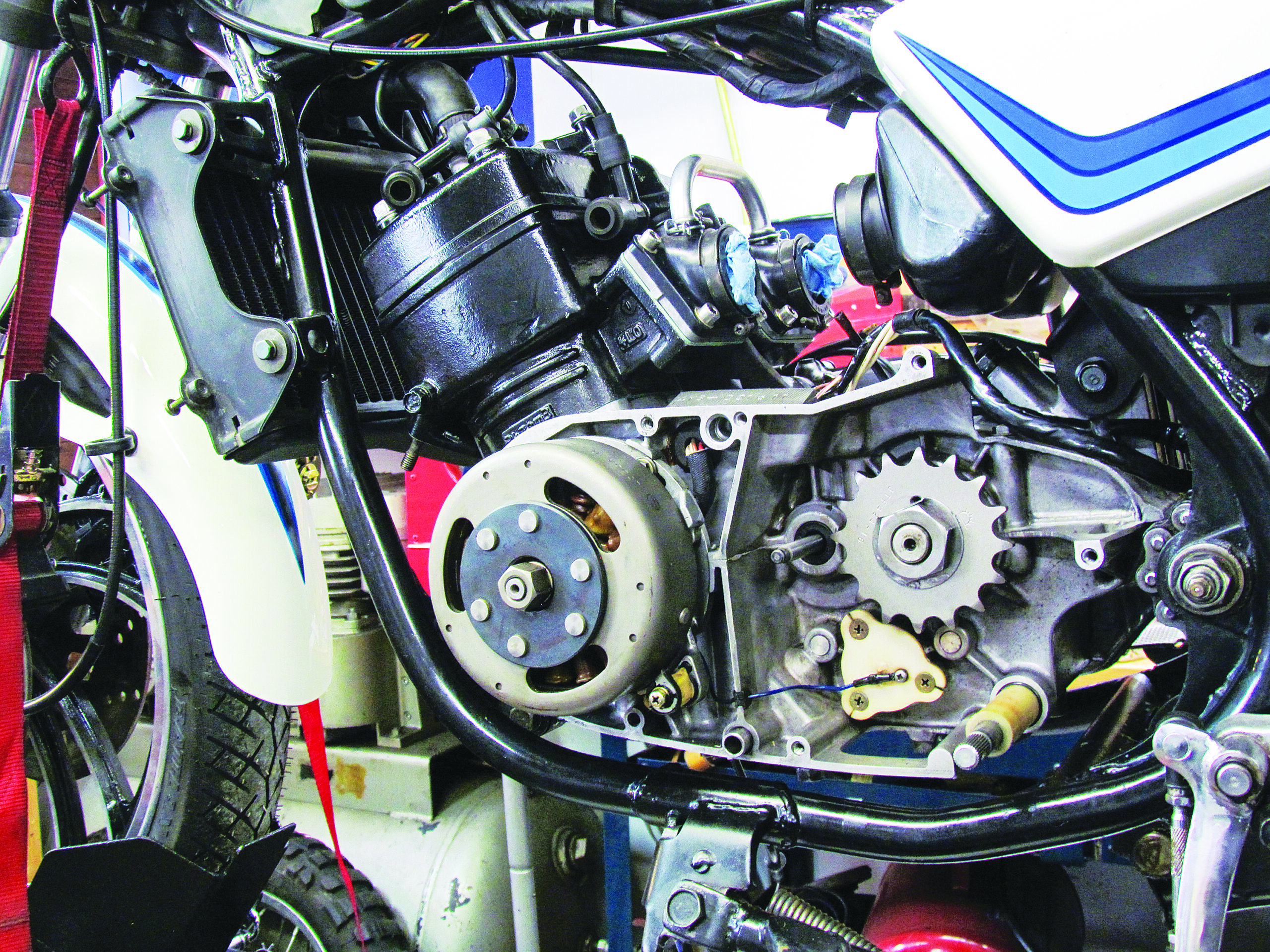

My friend Carl’s RD350LC was running poorly, and it was discovered that someone had previously rebuilt the engine and damaged a main seal upon reassembly, causing a massive crankcase leak. I at least like two-strokes enough to repair them, so please, no hate mail.

Thanks for Reading

If you don’t already subscribe to Motorcycle Mojo we ask that you seriously think about it. We are Canada’s last mainstream motorcycle magazine that continuously provides a print and digital issue on a regular basis.

We offer exclusive content created by riders, for riders.

Our editorial staff consists of experienced industry veterans that produce trusted and respected coverage for readers from every walk of life.

Motorcycle Mojo Magazine is an award winning publication that provides premium content guaranteed to be of interest to every motorcycle enthusiast. Whether you prefer cruisers or adventure-touring, vintage or the latest models; riding round the world or just to work, Motorcycle Mojo covers every aspect of the motorcycle experience. Each issue of Motorcycle Mojo contains tests of new models, feature travel stories, compelling human interest articles, technical exposés, product reviews, as well as unique perspectives by regular columnists on safety or just everyday situations that may be stressful at the time but turn into fabulous campfire stories.

Thanks for considering a subscription. The Mojo team truly appreciates it.